Lessons Machanic Manyeruke’s Story Holds for Understanding Matters of Culture & Faith, Church History . . . and More

How Music Can Nourish Any Soul (How this film came to be)

I first came to know and love Machanic Manyeruke’s music while doing research and then filming for an extensive documentary film project exploring the sources and directions of Christianity’s explosive growth in Africa filmed in Ghana and Zimbabwe. Doing preproduction research in Zimbabwe in 1996 I found myself traveling around the country to different locations listening to his and other local gospel musicians’ songs. Gospel music had become wildly popular by then in Zimbabwe, and Manyeruke’s songs especially. Translator/guides driving with me would translate the lyrics of his songs (almost all in the local Shona language which I didn’t know) and, in time, while driving alone, I found myself singing the choruses along while listening to them. And, though in Shona, I felt them nourishing me spiritually, which seemed remarkable! Several years later, while doing major filming for the project in 2000 I continued to listen to his music, and would hear his songs being sung in a variety of local churches where we filmed, for example in St. James United Methodist Church in Dangamvura township outside Mutare, where it was sung from memory by all as a normal part of prayer time in regular Sunday worship. Click image below:

Over a decade later, in 2011 when I returned to Zimbabwe to do follow-up filming for that project—delayed by funding issues and dangers posed by political violence in Zimbabwe—I finally got to meet the Baba (“Father”) Manyeruke. I was immediately impressed by his extraordinarily good character– among other things, his humility. Later that year, when he was scheduled to make his first visit to the United States to perform for a couple Zimbabwe communities there, I helped organize two concerts for him in the Northeast, filming them both, and hosting him in our home in Northampton, Massachusetts. After one concert I decided to sit down and film an interview with him about his life and it was then that I immediately came to see that his life held important, even profound, lessons for understanding Christian growth around the world, and, more generally, matters of culture and faith.

Urbanization and Church Growth

To begin with, the story of Machanic’s having to leave his home village to the city on his own to find work at the age of 14, after his father dies and no one comes through to pay his school fees, is a classic Christian story. It is much like that of figures like Dwight L. Moody, for example, who, after his alcoholic father died, had to seek work in the city as a youth and then went on to become America’s great evangelist in late-19th century industrializing and urbanizing America. Negotiating the anonymity of city life, without family tightly around you in village life, both providing for you and controlling your ways, holds many challenges. Among them, anomie, or normlessness, hovers everywhere, and needs normally met by wider family relationships cry out to be met by others. And it is here that new communities called “church” spring forth to meet such needs, providing supportive relationships and a moral compass for the new life of the city.

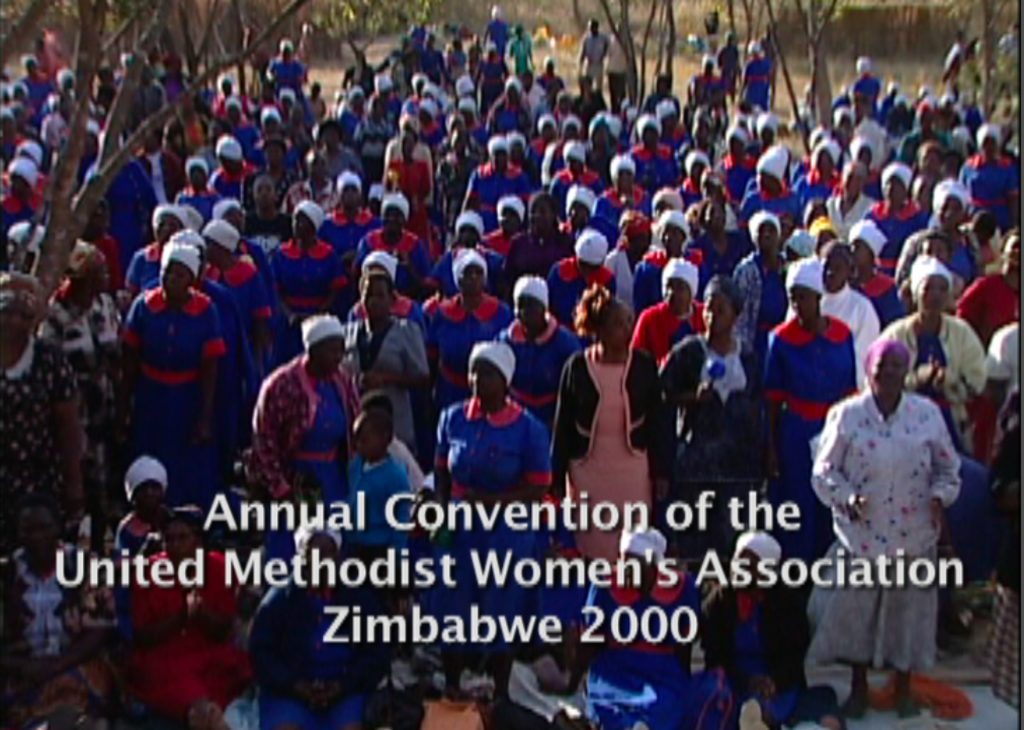

In fact, church growth tends to take off in cities. Pioneering mission work in Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) by missionaries largely from England and the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for example, didn’t achieve rapid church growth until city growth unleashed it, especially after World War Two. In the 11 years between our filming St. James United Methodist Church shown above in 2000 singing “You Pray for Me! I’ll Pray for You!” and our return to do follow-up filming there in 2011, St. James had given birth to three new congregations in the rapidly growing township of Dangamvura, all filled to the brim on Sunday mornings.

In the United States, during the rise of fundamentalist Christianity fueling the New Right in the in the 1970s and 1980s, many observers were surprised to learn that fundamentalism did not begin in the American South, but, instead, much earlier, in the late 19th century in the new industrial cities of New York, Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles. It was only in post-World War Two America, with the growth of New South cities like Lynchburg and Virginia Beach, that fundamentalist Christianity became a powerful force in the South. Even in 21st century America, as J.D. Vance observes in his recent book Hillbilly Elegy on Appalachian conservatism and religion, Vance’s rural relatives, he observes, though quite spiritual, were not generally active in church. Instead, those relatives of his who had moved to cities for work, were committed church-goers.

The reason for this is that people leaving their rural homes, where extended-family and village-like neighborly relationships give support and social and moral foundations, find that in the impersonal anonymity and individualism of city life they need new forms of community to meet those needs, and church communities often step in to meet them. The proverbial saying in modern American life “It takes a village to raise a child,” points to these fundamental realities. In a village everyone has that formative support (and control) around him or her . . . and takes it for granted. In the city it is gone! . . . a hard thing to fathom. What Machanic confesses he thought when pondering his move as a young man to Harare–that in a big city “you’d just go and relax and maybe sit down, and somebody could give you anything you want”–points to how unfathomable such realities are between such different contexts of life: village and city! Machanic laughs looking back at the irony of his mistaken outlook back then. But, it is interesting to note that in imagining this, Machanic is actually projecting an assumption of village life onto what he imagines city life to be: that when you are there, people around you will actually notice you and care for your needs, in great measure given the abundance of things observable in the city.

How churches step in to meet such needs for material support and moral orientation in city life appears in Zimbabwe’s United Methodist Church, for example, in its lay-led prayer group movement, and in the close fellowship of neighborhood Section Groups meeting each week. Both provided material, social and moral support for members in need, like the widowed school teacher, Mrs. Bwawa, featured in our documentary film, African Christianity Rising: Stories from Zimbabwe. (For a look at the weekly fellowship of Mrs. Bwawa church fellowship, click the video below.)

In the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, one of Ghana’s historic mission founded churches, exponential church growth in the post-colonial era was fueled mainly by lay-led Bible Study and Prayer Groups providing similar support in urban life, stepping in, for example, to meet the counseling and material costs involved in a young person’s wedding and marriage launch, things normally provided by close kin in rural communities. It was a lay-led Bible Study and Prayer Group, for example, made up mainly of science teachers in the local high school, that founded and led Grace Presbyterian Church in Akropong, Ghana, which through its pioneering deliverance ministry grew to become that denomination’s largest church. In addition to their efforts to determine any spiritual sources of peoples’ problems and invoke the Holy Spirit to overpower them, members would offer personal counseling and support, even taking young persons into their homes to care for them. For example, in the video below portraying the weekly work of the Bible Study & Prayer Group’s Deliverance team, the woman who speaks of problems in her marriage was being sheltered and cared for by her Aunt Agnes, the biology teacher and team member who testifies to having learned a lot about “the work of demons–how Satan operates.” The teenage boy who says he has a drinking problem, to take another example, was taken into the home of the Deliverance Team’s leader, Prophet Abboah-Offei, also a biology teacher, whose family cared for and mentored him. The boy, Samuel Amankwah, went on to become a renowned prophet with his own megachurch in the capital of Accra. Finally, the seamstress, Oye, who moved to the provincial city of Akropong for work, found herself in difficult circumstances when her brother, who had been helping her out, lost his job. Grace Presbtyerian’s Bible Study & Prayer Group sought to help her develop her seamstress business some. These are just some examples of how church communities provide care and support in the impersonal world of city life. (Click below to watch that excerpt from African Christianity Rising: Stories from Ghana.)

Ghana, 1998

As for America’s Dwight L. Moody, as a youth working in an uncle’s shoe store in Boston, it was the outreach of a Sunday school teacher who came to him one afternoon in the back room of the store, put his hand on his shoulder and spoke to him of Christ’s abiding love for him. The caring outreach of that man, perhaps meeting Moody’s need for fatherly love, his biographer thinks, moved him to a transformative spiritual awakening. (Lyle Dorsett, A Passion for Souls, p.47) A year and a half later, in 1856, when Moody moved to the young rapidly growing railroad city of Chicago to seek his fortune, he was eventually motivated to do the same, reaching out to help poor children among the growing number of working families migrating to Chicago. His mission connected him with the growing YMCA movement and the Salvation Army, which both emerged to meet such needs in the new industrial cities of America and England. Moody’s ministry was such a major force in American life at the time that when newly elected President Abraham Lincoln met Moody in Chicago, he said to him, now I’m meeting someone famous.

In Machanic’s case, it was the outreach of a Salvation Army worker that brought him as a young man working in Harare (then Salisbury) into the supportive fellowship of a Salvation Army congregation. He was on the way home where he was working as a gardener for an Australian couple in the white suburb of Borrowdale, after seeking some company with other young men at a beer garden in the township of Tafara. It was one of his first experiences drinking beer, Machanic remembers, and he was feeling “a bit drunk” when he crossed paths with Peter Bomba, a Salvation Army worker, who reached out to him.

“Where are you coming from, my young man?” Machanic recalls him asking. “You’re like maybe drunk somehow. How can you do this, a young man like you?” Having been raised as a Christian, having worshipped as an Anglican and attending St. Paul’s Anglican school near Gweru, Machanic asked Mr. Bomba to pray for him and asked where they worshipped. “Under that tree over there,” Bomba explained, pointing to a tree nearby.

Machanic ended up joining that Salvation Army fellowship where he found support, counsel and opportunities to develop his musical gifts for worship. His first ministers in the Salvation Army, Thomas and Syria Kagoro, recall that Machanic, in turn, became a music teacher and mentor to many young people in the Salvation Army, who called him “father,” including some of their own children. According to Machanic’s biographer, Bornwell Choga, his popular reputation as “Baba” (“Father”) in Zimbabwe public life, stemmed from that role of his teaching youngsters music in church.

Machanic’s story, like D. L. Moody’s, then, is a “classic” Christian story, though over a century apart. And like Moody, Machanic ends up devoting himself to meeting the needs of young people facing the kinds of challenges he experienced as a young man in city life. Stepping in as father or elder to young people in need of such in their urban lives is still strikingly evident in Machanic and his wife Hellenah’s relationships with the young musicians he now works with, as well as with youth members of their Salvation Army congregation. Maxwell Barson, for example, the biology professor who now serves as a lay leader in that congregation, testifies to how Baba Manyeruke “groomed” him and made him who he is today. Then, when his first wife died, he remembers Baba stepping in to counsel and support him.

As far as Baba’s young music team goes, you see them calling him “Daddy” and Hellenah “Mom” and turning to them for counsel and support. Vocalist Melynda says she doesn’t think she and her husband, Jonathan, would still be together without Baba’s counsel and support. For his part, her husband Jonathan, the group’s keyboardist, sound engineer and vocalist, credits Baba for teaching him “a lot, even how to run a family . . . how to talk to your wife, to care for your children.” This points to new forms of marriage and family life emerging and taking root in the fundamentally different conditions of city life, a subject we will turn to now.

Changes in Marriage and Gender

Leaving the close-knit supportive, yet also controlling, web of relatives in rural village life, for city life, creates challenges that prompt significant changes in marriage and family life. In this film’s few scenes of rural life, one sees women and men sitting separately when they eat, and working separately in the fields. Where extended families are the building blocks of life, they generally involve some degree of gender segregation, creating women’s and men’s worlds. For example, women often rely on other women kin to manage household things, care for children, etc., rather than their husbands. For many working people following their relatives in chain migration to cities for work, this pattern of extended-family life, and the gender segregation associated with it, can remain strong. For some, especially those forming a professional middle-class, those patterns can give way to a more nuclear family pattern, and a closer companionship between husband and wife, termed by sociologists a “companionate” marriage.

Compare, for example, Jonathan and Melynda’s pattern of life, going out to work together, for example. “He’s become my best friend,” Melynda observes, noting that people watching them together tend to assume they must be brother and sister, rather than husband and wife, quite simply because such companionship is not expected in marriage by many. Even in Kenya, quite recently, it was considered improper for a husband and wife to kiss or hug each other in public.

To continue, go to p. 2 here.

Important Lessons about Contextualizing Christian Faith

Since music plays an important part in Christian worship and Christian life, it is to be expected that it would play an important role in the process of contextualizing, or bringing Christian faith into, local Shona culture. As a pioneering popular gospel musician—so much so that many call him the “father” of gospel music in that nation—Machanic’s music plays an important role in that contextualizing process. Of course, singing songs in Shona rather than English was one big step, going against the colonialist prejudice spoken of by his producer at Gramma Records, Bothwell Nyamhondera, that “to do things right, you had to do them in English” . . . even if worshippers didn’t fully understand, or understand at all, what was being sung!

But, in addition to language, grounding Machanic’s songs in local rhythms and instrumentation, including drumming, brought them more powerfully into the spiritual life of Shona people, like the mhande-like rhythms Machanic enjoyed following his father’s traditional mhande music. But, the association of such music with the traditional spiritual life of the Shona people–for example, the song and dance performed by the Mhande dance ensemble at Zimbabwe’s College of Music, appealing to Tovera, the spirit of one the great founding ancestors of the Shona people, to bring rain–often led missionaries to ban any such music from church life.

In addition to traditional Shona music, popular rhythms from other parts of Africa—like South Africa, the Congo and Kenya, for example—also became part of popular Zimbabwean musical styles and were banned from churches. For instance, sungura rhythms, influenced by rhumba rhythms from the Congo and by other local styles in Kenya, were picked up by Zimbabwean refugees in Kenya fleeing liberation war in their homeland. They brought them back to Zimbabwe where they became very popular, but fiercely banned by most churches. Mono Mukundu, a musician, music producer and close colleague of Machanic’s, recalls the kinds of experiences he and other gospel musicians had performing gospel songs with sungura and other popular rhythms in many church settings. Click image below.

Rhythms that called for dancing, in particular, or other bodily experience and expression of the spirit, were often rejected for that very reason. However, it is important to note how fundamentally important communal dancing to music is to the spiritual lives of Shona and many other African peoples. Not just singing, but moving bodily to music all together, represents important ways of coming together in spirit. Notice how Machanic’s older sister Luciah recalls with him as they revisit his birthplace, how they used to routinely dance together with other neighbors there, and her distinct memory of when one family’s daughter was possessed by some spirits of their ancestors. And in the brief clips of Machanic performing in a 1980s gospel concert in Harare, notice how enthusiastically all present are taken up dancing together. Of course, dancing’s connection to spiritual powers of different sorts is an important reason for Christian leaders’ wanting to distance converts from dancing itself. Yet, European Christians’ uses of their own pre-Christian practices–in traditional winter solstice celebrations turned into Christmas, for example–while, at the same time, looking down on Africans’ employment of their own traditions, played an important role here.

It would take time for dancing–even in more modest, “nice” forms–to become accepted in church life. The Salvation Army, in its historic birthing in England, under the leadership of William Booth, pioneered in bringing popular brass-band music from working-class England into worship, a mission Booth expressed in the famous adage credited to him, “Why should the devil have all the good music?” (of course, thereby, condemning as “devilish” the contexts, including pubs, where such music was created and enjoyed). However, in Zimbabwe the Salvation Army still seemed to keep a wary eye on too energetic dancing during formal church worship services.

Many western churches, for generations, of course, accepted the organ as the only proper instrument for worship music, though unaware of the fact that the organ was first invented in Egypt and used, because of its powerful sound, to express the voices of the spirits of deceased pharaohs. They would be appalled to learn that it was brought to Rome, where it would eventually become the music of the imperial church, by Nero, who originally used it to prepare Christians for sacrificial gladiatorial combat. What a legacy!

Machanic found that the Salvation Army’s brass band music with drums had some appeal to him. The Salvation Army even permitted guitar-playing with their brass bands outdoors for Christmas festival, outside of formal worship. Machanic felt because of his popular Shona chorus Ari Mandiri (“He Is Within Me”), he would be allowed to play the guitar in church. And, as his biographer, Bornwell Choga notes, he pioneered in bringing guitar music into the Salvation Army.

Of course, there were pioneering efforts to introduce Shona language, and local music styles, in other branches of the church in Zimbabwe. Father A. M. Jones in the Catholic Church and Robert Kauffman and the Wabvuwi in the United Methodist Church fostered important work in that regard. (Ezra Chitando, Singing Culture… pp. 30-31.) And independent churches, like the Zion Apostolics or Zion Christian Church, who had freed themselves of European control early in their formation had freely introduced local Shona music styles and dance into their worship (though shunned and considered non-Christian by mainline mission-founded churches as well as new charismatic ones). I enjoyed filming a group of Zion Apostolic men leaders at one of their annual Passover festivals discussing with intense enthusiasm their appreciation of Old Testament discussions of the Israelites dancing with tambourines in circles to praise God. They and their assembled followers did that in their regular ways as part of worship later that day and all through the night. (Click image to play.)

(It is interesting to note that when the Zimbabwe Fellowship of New England is enjoying Manyeruke’s music as he performs for them, they are dancing in a circle together.)

The Prominence of Spiritual Healing

On the multi-denominational stage of popular Christian music, Machanic was one of the important, though not the only, pioneers in bringing Zimbabwe-style gospel music with Shona lyrics into the limelight. But, there are other dimensions to the popularity of his music that hold some important lessons about the process of contextualizing, or rooting Christian faith authentically in local Shona culture. That can be seen in those songs of his that seemed most popular among enthusiastic Christian followers of his music, songs they would always call on him to perform in local concerts, and songs, because of their sustained popularity, he would remix again and again for new CDs. They are ones that he performs in our film to his Chitungwiza Citadel church community and to the Zimbabwe Fellowship of New England in Worcester, Massachusetts. Have you noticed what themes they often carry?

Three of Machanic’s most popular songs from early in his career, and to this day, I noticed, emphasize similar themes. One is Rudo Serwa Peter, a “Love Like Peter’s,” telling to story of Peter and John healing a crippled man they meet at the temple. Another, Moses Murenje, “Moses in the Wilderness,” tells the story of Moses, whose people were suffering from poisonous snakes. Moses lifted up a brass sculpture of a snake and when they looked at it, they were healed. Jesus cited this event and likened it to his own life’s mission to save and to heal, which Machanic includes in this song. (It bears mentioning that coming across a poisonous snake which threatens was a reality Shona people could easily recognize.) Finally, perhaps Machanic’s most popular and most remixed song, which leads off his popular Best of… album, Madhimoni, or “Demons” in English, tells the story of Jesus casting out demons from the viciously possessed man, Legion, at the graveyard. In its original version, Machanic tries to make the gospel story of Legion crystal clear by breaking into the spoken word in the middle of the song to lay out the basic facts of the story through Jesus exorcizing the evil spirits and sending them into a herd of pigs nearby.

All three of these most persistently popular songs of Machanic’s happen to bring to the fore elements of Jesus’ and his disciples ministry that had been sidelined, if not dismissed, in the Post-Enlightenment worldview of most western missionaries bringing Christianity to Zimbabwe and, more widely, to Africa as a whole. The Post-Enlightenment outlook of the educated West, dominated by the empirical sciences as ways of knowing, focused on the empirical—what could be seen, felt or touched—and had no place for the invisible effects of spiritual powers or realities. Within that outlook, spiritual healing or the effects of spiritual powers, had no place, and were dismissed. However, in Shona and most African cultures, you can’t be a religious figure and not heal, and afflictions caused by evil spirits are considered a normal feature of life.

Machanic’s songs like Madhimoni, Rudo Serwa Peter, and Moses Murenje, performed routinely for more than thirty years now, as Maxwell Barson, the biology professor, notes, and remixed in new albums again and again, helped bridge that gap created by the prevailing Post-Enlightenment worldview of western missionaries who didn’t teach spiritual healing or exorcism, while both were pervasive in local Shona and Ndebele cultures, and in sub-Saharan Africa as a whole.

Machanic’s fellow music leader in their Salvation Army congregation, Beauty Sithole, notes that “He was the first musician who told that you could come and see what God has done: he has just lifted up that crippled man to walk!” “That’s one of his best songs,” she adds, noting tellingly that “His songs don’t fade out.” Madhimoni was the other song she mentions in that regard. So bridging the gap left by western missionary teachings, was something that appealed powerfully to Zimbabwean Christians across denominations and over more than a generation.

I wondered if Machanic himself felt specifically moved—though perhaps intuitively—to help bridge that gap, writing songs which met felt needs. So, I asked him. He told me that early in his career when he was generally performing alone and writing songs, he was often called to local churches or meetings of Scripture Union, a Christian fellowship for youth, often for students in boarding schools, which served as a powerful vehicle for evangelism and church growth in Ghana as well as Zimbabwe. In those contexts, he recalled, he found himself inspired by what was being preached, and that often found its way into his songs. So, he might simply have been inspired by what biblical stories local preachers and teachers felt were most needed to convey to new converts or believers the realities Jesus’ ministry.

Their eagerness for songs about spiritual healing is reflected in the fact that, when Machanic was called by Bishop Abel Muzorewa, then head of the United Methodist church in Zimbabwe at the time, to come sing at his large church in Harare (Salisbury at the time), which was a major break for him onto the public stage, it was that song Rudo Serwa Peter that Bishop Muzorewa wanted him, above all, to perform. This may have been motivated by Muzorewa’s desire to lift up the healing work of Jesus’ followers that tended to be set aside by the Western church leaders he always had to work with. (For reminders of how these themes of spiritual healing come up in Manyeruke’s music in the film, have a look here below at those segments carrying them.)

Even when spiritual healing isn’t a prominent theme in Machanic’s songs, it often finds its way into his lyrics, for example, in the last song appearing in the foregoing video: Vaimuziva Jesu (They Followed Jesus). Machanic sings, “I’ll keep singing about the crime you were charged,” about Jesus’ crucifixion, asking, “Was it healing the sick?” or “Opening the eyes of the blind?” to lift up Jesus’ everyday healing ministry. Or in his song “Ndinamatire Ndigokunamatirawo” (“Pray for me and I’ll pray for you”), sung in the video on this web age by St. James United Methodist church in Zimbabwe, one verse sings “Father Peter conquered with prayer” reminding people of Peter’s healing work.

Regarding Machanic’s ever-popular song Madhimoni, even twenty-some years after it became a hit, in the early 2000’s, when I showed leaders of Global Ministry in the United Methodist Church at their offices in New York City footage of all-night worship with spiritual warfare at the annual women’s fellowship revival of their church in Zimbabwe, several spoke up in wonder and puzzlement that they had never seen anything like that (even after many visits there). It turned out that was simply because their Zimbabwean partners routinely made a point of not taking them to such events, because they were aware that such work of spiritual warfare would disturb them and that they, in turn, might disturb the normal course of prayer and worship there. (For a glimpse of that all-night worship event among United Methodists in Zimbabwe that American visitors generally did not attend, click the video below.)

To continue go to p. 2 here.